Why Do We Meditate?

The Tensegrity of Discipline

Our contention is that meditation calibrates basal neuronal function: it tonifies the limbic system such that you freak out less; it calibrates the proprioceptive system such that you become less clumsy; it clarifies the boundary conditions of parasympathetic activation such that you spend less time oscillating between poorly defined rest and activity; it retrains thalamic modulation of narrative consciousness such that the reward calculations so typical of the forebrain realign to healthier vertices. All of which means we become calmer, more competent, more decisive, more energetic, and more willful and purposive in all things. I lay emphasis on the fact that meditation is effective to the degree that it targets the lowest-level and thus highest-priority systems: the effects percolate upward. Meditation is sanctimonious garbage to precisely the degree that it promises to make you holier-than-thou, that it targets your "highest" nature, that it encourages fantasies of transcendence and otherworldliness - in other words to the degree that it targets social reward calculation, unresolved parental imago and Oedipal entanglement, and everything which hints at penance and reward, trial and judgment, acknowledgement and love. Meditation is not about proving yourself worthy to a withholding god, nor besting the haunting voice of your father, nor winning back the first embrace of your mother. You will never win that game, because the solution is not within the game: these hangups will arise in meditative practice with a renewed force, but they must be attacked from a different angle - namely symbolic analysis. Part of our ambition is to point the way out of the snares laid for millennia by the priests: they claimed ascetic practice and made it their own; they perverted the exploration of the bleeding edge of human potential into just another means of instinctual castration. This is why the early Daoists are such a precious testimony: they were relatively untouched by the priestly agenda and maintained the pride and rigor of hermitage as an antithesis to priestly ambitions. Why solitude? Why is solitude an essential ingredient in the recipe of maximal human development? Because social reward calculation is our stupidest, loudest voice: it makes us into abject groveling fools. It preys upon our deepest wounds. Living in a state of civilized tribelessness, such as we do, exposes this fundamental weakness of human character: only a deep and abiding acceptance of isolation can defeat it. What is generally not known or expected, is that just as often, an almost unheard-of richness of companionship lies on the other side of such solitude: there are more of us than there may seem.

Why do we meditate? Because we want to become something more. Why do we hesitate? Because we fear the consequences. Growing up into the containment of our potentialities, fleshing out the skeletal frame of our emotional constitution, growing accustomed to the sensation of productive freefall can be just as frightening as not getting what you want - indeed much more so. Because what comes next is undecided, uncharted, unfelt. Most of us prefer the worst of what we have already known, to the possibility of a novel indeterminate experience. Therein lies my last claim concerning the powers of meditation: it will strengthen your tolerance of ambivalent novelty. It's possible to trace the trajectories of pleasure and pain, joy and sorrow, desire and repulsion back to where they first diverged: there is the ecstasy of being alive.

Neurochemically there doesn't seem to be anything quite like meditation. It's like waking from the perfect nap without grogginess. The stomach is settled, the muscles are relaxed but ready, the mind is clairvoyant and childlike, the mood is buoyant and receptive, yet also serious and mature. I can't list the ingredients of this neurochemical cocktail - but I can tell you how to cook it.

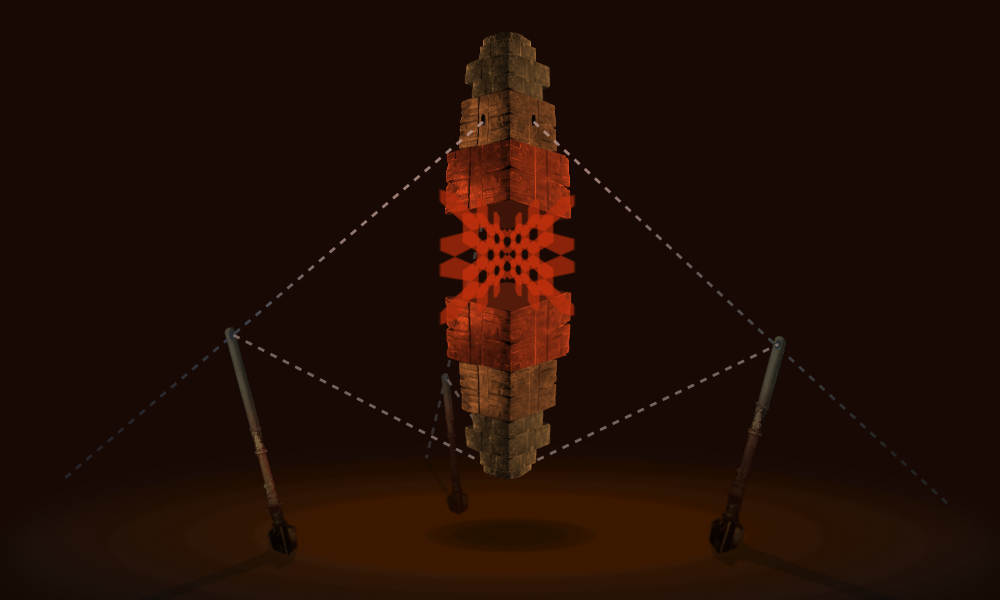

Emotional reparations gained from meditative practice: to provide a "holding environment" as the ego psychologists say, in absence of the kind of emotional stability one should have had in childhood. To learn to deal with the sense of perpetual loss and abandonment which characterizes modernity. For some of us with too much integrity and introspection to have been candidates for narcissism, we learned to develop the meditative arts as a kind miniature community - never losing sight of the fact that the primary function of so-called "narcissism", is to generate a small manageable tribe: the gazing lover, the beloved image, and the threatening reality. In vigorous meditation, you have the practitioner, the practice, and everything which resists the practice: in other words, your devotion, the ideal, and your perpetual failure. So much of what's valuable in genuine meditation instruction, are the tales of successful failure: or how get the ideal to switch places with your failure, and the failure to switch places with the practitioner. Good meditation happens when there's a kind of "tensegrity" between all three elements.

I have meditated seriously and daily for more than 20 years. The first 2 years of practice changed my life permanently. I set up a little hermitage in my overeager youth, and aside from earning a little money to support myself - as a construction worker comically enough - I practiced nothing else. On good days I would manage an honest 3 hours of concentrated practice. I followed a cycle I could repeat as often as possible: exercise, bathe, meditate, eat. For a brooding, overintellectual, uptight white boy - it was a revelation. I discovered spontaneity and physicality, I discovered an emotional life, I discovered self-love, I discovered the intoxicating power of concentration and stillness. But eventually it faded, and like all intoxicants the highs no longer satisfied. I grew intensely restless: doubt and disenchantment began their long campaign...

Years later, I still practice. Why? Because it's a form of hygiene. Meditation for the all-too-modern human being is a matter of spiritual cleanliness. Nothing is so necessary to the overwrought mind and the underutilized body as a little vigorous stillness. Thus I insist that the benefits of meditative practice have more to do with refinement of unconscious process, rather than yet more overexploitation of conscious acrobatics.

Our best spiritual development will not be found within yet more anxiety-conditioned self-awareness, yet more half-therapized consolation, yet more moral posturing before a mirror of blamelessness. We must learn to properly align and exercise the system as a whole: what we want is the analogue of "athletic heart syndrome" in our bodymind. How do you obtain this kind of easy stillness? Not by "abandonment of desire", nor "insight", nor any moral obedience - but by exploiting nonlinear emergence via conditioning of the many unconscious subsystems, which produces a far greater yield of intelligent behaviors at the conscious niveaux than the usual topdown approach.

Insight is not the cause of enlightenment, it is a product of health.

Meditation is no panacea. But according to even the most trenchantly hostile cognitive psychologists, there are a few uncontested benefits of meditative practice:

- Reduced stress

- Improved anxiety tolerance

- Enhanced learning ability

But if that were all it accomplished, it would not be worth its mystique - and we might as well substitute pet ownership and a daily exercise routine: which is precisely something agents of the status quo would like to insinuate. But they'd rather see you a drug addict: have no doubt that their pails full of pills will be brutally effective...

Why do we meditate?

- It stills the blabbering narrative mind: overcoming the tendency to fill every ambiguous space with useless talk is the first challenge.

- It awakens the body: an enhanced proprioceptive capacity makes "being-in-the-world" more interesting than a droning monologue.

- It repairs an overloaded nervous system: unlearning the habits of repressive psychosomatic quarantine, replacing afferent garbage-hoarding with informative parsing and efferent garbage-disposal, is one of the crown jewels of meditative practice.

- It teaches intuition: a cultivated attitude of curiosity, patience, and humility before the present moment makes us much more receptive to unconscious intelligence, and thus the totality of latent neuronal brilliance, than the typical arrogance of the loud, clinging, noun-munching conscious posture.

- It develops emotional independence and equanimity: the more often the chasms of indeterminate multivalence are faced, crossed, plumbed, the less we panic in the presence of novelty.

What are its contraindications?

- It tends to induce hypervigilance. It can initially worsen the overactive mind and under certain circumstances, lead to a greater proclivity to anxiety: the collapsing roof of an overly ambitious structure with bad foundations - a commonality among some of the most talented students subjected to the badfaith teachings of the priests, who need to enfeeble their strongest rivals.

- It can lead to obsessive self-monitoring. It encourages the illusion of control through maximum sustained consciousness: in the mediocre students, this leads to premature delusions of mastery.

- Genuinely exotic experiences can be abused to encourage fables of "contact with divinity", absorption into "pure consciousness", and other fantasies of transcendence and spiritual hierarchy.

What does meditation impart? A growing sense of agency, a deepening appreciation of the body, a burgeoning gratitude toward the shimmering world, an unexpected mastery of sensorium and mood, and a rare relief from the sense of victimhood which has a contagious quality in our age. Let me say it again for the hard of hearing: sitting still and paying attention to your breath, will disincline you to passive lazy behavior. It teaches discipline at a level to be found nowhere else, because it demands it at a level to be found nowhere else: thus am I so hostile to the portrayal of meditative practice as just another consolation of a helpless wretch, just another stopgap in a hopeless case, just another day at the spa, just another indulgence of a bored brat.

Meditation is often misunderstood as a kind of stupor. But it's a willful mischaracterization: there's a long history of Eurocentric slander of "oriental laziness" aimed at this discipline, which would like to hide its own terrified workaholic escapism behind the name of virtue, and employ as many gravediggers as there are ambiguous feelings, desperately avoiding contact with stillness because it is so ambivalent and potently associative.

True sitting meditation can be the most difficult task of all: actively, willfully sitting still and paying attention to breath and body. Even 20 minutes of this discipline, daily and successfully performed, requires years of practice. Dedicated practitioners know only too well that years can slip by "on the cushion" without any signs of progress.

Moreover, meditation is easy to fake. Most of the braggarts in this art - and they are the rule - get no further than endless discursive thinking, rambling and reactive feelings, gratifying fantasy chasing after fearful anxiety, a chaotic body alignment, and so on. Realistically assessed, a 30 minute session is often highlighted by a two minute stretch where one finally settled down and decided it was time to meditate. One minute of total concentration is enough to give the beginner extraordinary visions and ineffable feelings. If you don't believe me, try it. Be honest with yourself and observe how long you can remain focused without beginning an internal dialogue. It will be a very short time.

Where are these "siddhis", these magic powers we were supposed to obtain? But relative to the average modern slob, we do obtain magic powers: freedom from pointless worry, the ability to know what one is feeling at any moment, the presence of mind and body not to make stupid mistakes, the quiet of mind not to commit unconscious acts of neurotic revenge on oneself and one's family, the ability to know what one wants, the courage to allow annihilating insight, sufficient experience with spiritual vertigo and the sense of falling apart such that one no longer resists it, and of course the ability to read other people like the open books they really are...

But even after all that's in place, there's still the much greater difficulty of giving oneself permission for this power: what will we do with it? To what end? Everything depends on trusting ourselves to be responsible and worthy of the imbalance of power, whether we feel "compassionate" or not...

What is meditation? Remedial training in physiological homeostasis. Cognitive expansion through entrainment to the rhythms of the breath, the heartbeat, the musculature, and the digestive tract. To learn a skillful balance and responsiveness to the many sources of information of the body-collective... All of which we were supposed to have learned as children, and all of which any healthy animal in the wild knows to its bones. To work and play hard, without ever straining oneself; to learn how to rest frequently and at every available moment; to learn how to minimize effort wherever possible and only maximize at the critical juncture... This begins to sound like training in martial arts, and perhaps that's precisely correct.

常にも兵法の時にも少もかはらずして心を広く直にし、 きつくひっぱらず少もたるまず、 心のかたよらぬやう心を直中に置て心を静にゆるがせて、 其ゆるぎの刹那もゆるぎやまぬやうに能々吟味すべし

In both everyday and military events, your mind should not change in the least, but should be broad and straightforward, neither drawn too tight nor allowed to slacken even a little. Keep the mind in the exact center, not allowing it to become sidetracked; let it sway peacefully, not allowing it to stop doing so for even a moment. You should investigate these things thoroughly.

Miyamoto Musashi, 五輪書, 水之巻

Meditation is remedial training in feedback modulation. It reinforces our most ancient instincts of homeostasis: overlapping intertwining rhythms of breath, heartbeat, peristalsis, the subtle undulation of mood, the "gently swaying mind".

Meditation restores our birthright to the healthy, well-rested, well-exercised body which every exuberant puppy, every napping cat, every flitting sparrow, every lizard in the sun practices every day. While it's true that we thought we were climbing a mountain, when it turned out we were only digging our way out of a hole - that does not mean however, that this plateau of health should be considered "normal" in any modern sense! I will forever advocate for the "enlightenment of animals" as the proper paradigmatic orientation of our spiritual life. A quiet but alert mind, a relaxed musculature, the ability to fall asleep whenever necessary, the freedom from excessive inhibition and the readiness to fight, flee, mate, care, abandon, eat, and rest - all in proper proportion.

What we get in meditation is a foundation of subjectivity more stable than the echo of the last conscious sentence: a glowing ruminant interoception, the topological undulations of proprioception. It comes not from without or "above" or "beyond" and it definitely is not "consciousness itself", it is the peace of the healthy intestines, the functioning liver, the muscular heart, the confident idling nervous system... Only in this condition and no other, can the as-yet-unknown potentialities of maximal human development be explored: only via a renewed homeostatic foundation, can we find out just how smart we are and what we want to do with it.